All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Giant Fibrovascular Vulval Polyp in a Young Female: A Case Report

Abstract

Background

Fibrovascular stromal polyps (fibroepithelial polyps; FEPs) are benign tumors occurring in many parts of the body and are infrequently reported in the vulva. They tend to be small, but few present in giant sizes, which adds diagnostic challenges.

Case presentation

A 24-year-old female with a five-year history of a right vulval mass that reached a massive size (35×15×10 cm), complained of a large, painless, soft, pedunculated mass causing discomfort and interference with daily activities. On examination, the mass was firm, not tender, and associated with surface ulceration and infection. The mass was surgically removed and subjected to histological examination to exclude any malignancy. The observation indicated the presence of a fibroepithelial (fibrovascular) polyp; thus, follow-up was advised.

Conclusion

This case report has explored giant FEPs’ presentation, diagnosis, therapeutic approaches, and possible consequences, and comprehensively discussed the findings of earlier studies. A better understanding of giant FEPs can improve their management and guide prescription for tailored treatment, which must involve evaluation of the psychological impact on patient mental health for a comprehensive holistic patient approach.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fibrovascular stromal polyps (fibroepithelial polyps; FEPs), which are non-malignant in nature, commonly occur in various anatomical locations. They are typically located in the skin folds, such as the neck, armpit, breast, groin, oral cavity, bladder neck, and genital regions [1-9]. They impact approximately 25% of the population, and their prevalence rises with age [10].

FEPs exhibit a range of clinical manifestations, ranging from minor to big pedunculated tumors. FEPs are typically small in size. They are referred to as “giants” when they exceed 5 cm in any dimension [11]. However, some literature studies use a cut-off value of 10 cm to define giant FEP [12].

Vulvar occurrences of FEPs are uncommon, and the manifestation of giant fibroepithelial polyps (GFEPs) in this area is exceptionally unusual, as documented in the literature. As they are very big and affect nearby tissues, GFEPs cause noticeable symptoms, like vulvar distention and pain and problems with daily activities, thus limiting intimate functions [13].

Ulceration, hemorrhaging, and secondary infections have also been reported. In exceptionally large cases, lymphedema occurs due to impaired lymphatic drainage. The physical pain caused by GFEPs can have a detrimental effect on patient's body perception, resulting in feelings of anxiety and depression, thus imposing a psychological impact on their lives [14, 15].

We, herein, present the case of a young female who presented with a vulval mass for five years, and embarrassment and social restrictions have refrained her from early counseling.

2. CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old woman who was sexually inactive visited the clinic with a complaint of a large, painless, soft, pedunculated mass. The mass extended from the right labia majora to below the middle of the thigh and caused discomfort during daily activities. The mass progressively enlarged over a span of five years. There was a negative history of vaginal discharge, fever, weight loss, or issues related to the bowel or bladder.

The patient experienced menarche at the age of 12 and had regular menstrual cycles with a normal flow. Her previous medical and surgical records were unremarkable. The patient was a virgin with no prior history of sexually transmitted diseases, genital injuries, drug use, smoking, or alcohol consumption.

Local examination revealed a 35 × 15 × 10 cm soft, pedunculated mass extending from the right labia majora causing labial elongation and extending below the midthigh.

The patient had concerns that medical intervention might compromise her virginity. Due to religious and cultural restrictions and the associated taboos surrounding virginity, she refrained from seeking any medical guidance until the condition had grown to an intolerable size.

Upon local inspection, a soft, pedunculated mass of 35 × 15 × 10 cm was seen. The mass originated from the right labia majora, resulting in an extension of the labia and further extending to the midthigh. In an upright position, the mass was located a few millimeters above the patella (Fig. 1). The mass was warm to the touch, not tender, and had a layer of skin with two ulcers on top, measuring 2 × 1 cm and 1 × 1 cm, respectively, with a yellowish discharge. The mons and the labia on the opposite side appeared normal. The trans-illumination test yielded a negative result. There was no swelling of the lymph nodes and no connection with the inguinal canal. The general inspection yielded no notable findings. The hematological and biochemical studies yielded normal results. The ultrasound examination revealed no abnormalities in the pelvic or uterine regions, so the decision was made to proceed with immediate surgical removal of the tumor without a preoperative MRI or biopsy.

The mass was excised completely from its base and then ligated using Vicryl number 0 suture.

Resected perineal mass weighing 850 grams.

| Authors, Year\Refs | Age | Site | Size/cm | Duration | Presenting Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The current case, 2024 | 24 | Rt labia majora | 35×15×10 | 5 years | Ulcerating pedunculated mass |

| Korkontzelos et al., 2023 [16] | 45 | Rt labia majora | 10×13 | 2 years | Pedunculated, painless mass that was inflamed and ulcerated |

| Dura et al., 2023 [17] | 21 | Rt labia majora | 3×6×9 | 2 years | Painless mass causing discomfort and refrainment from sex |

| Martínez, 2023 [18] | 30 | Rt labia majora | 20×15 | 1 year | Pedunculated mass with pulling pain |

| Martínez, 2023 [18] | 36 | Lt labia majora | 7×5×5 | 1 year | A pedunculated mass associated with a pressure ulcer |

| Mulik and Acharya, 2023 [19] | 56 | Rt labia majora | 8×7.5×7.5 | 5 years | A pedunculated mass interfering with walking |

| Donata, 2022 [20] | 21 | Lt labia majora | 12×4 | 3 | A painless mass causing discomfort and refrainment from sex |

| Kurniawati, 2022 [21] | 23 | Rt labia majora | 16×11×6 | 1.6 years | A painless mass causing discomfort |

| Kurniadi et al., 2022 [12] | 28 | Lt and Rt labia majora | Lt 20×18×8 Rt 9×4×2 |

4 years | A painless firm mass with leukorrhea |

| Smet et al. [22] | 22 | Rt vulva | 15×11×4 | 11 years | A mass involving bleeding from giant pedunculated multiple finger-like projections. |

| Quinn et al., 2020 [23] | 24 | Rt labia majora | 5×6 | 2 years | Gelatinous polyp with ulceration and bleeding |

| Yoo J et al., 2019 [24] | 14 | Rt labia majora | 20×12.5× 3.5 | 3 years | A huge, exophytic, polypoidal mass raised from Rt labium majora |

| Rexhepi et al., 2018 [13] | 16 | Rt labia majora | 18×12×3 | 2 years | A giant polypoid mass interfering with daily activities |

| Kumar et al., 2017 [25] | 20 | Lt labia majora | 42×22×10 | 10 years | A giant mass preventing walking and interfering with urination |

| Chawla et al., 2017 [11] | 32 | Lt labia majora | 10×10 | 10 years | A pedunculated polypoidal painful mass associated with ulcer |

| Colak Elif, 2015 [26] | 43 | Lt perineum | 18×12 | 29 years | A growing mass with discomfort |

| Madueke, 2013 [27] | 21 | Rt labia majora | 18.5 | 6 months | A grapefruit-sized ulcerating pedunculated mass |

Local anesthesia was administered to the patient because she refused general or spinal anesthesia. After admission to the hospital, the patient was lithotomy positioned. The procedure was performed under aseptic conditions. The resection was carried out surgically, followed by ligation of the wide pedicle (2.5 cm). Adequate hemostasis was achieved (Fig. 2). The patient was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanic acid at a dosage of 1 gram orally twice daily and was discharged after a few hours. After a period of two weeks, the patient came for a follow-up visit; the examination revealed a fully healed wound without any complications. The patient expressed satisfaction with the outcome. There was no sign of recurrence.

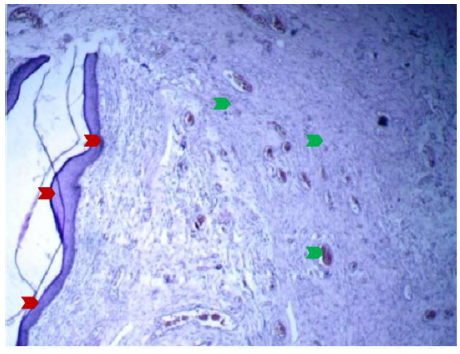

Microphotograph showing benign-looking squamous epithelium (red arrow) with underlying fibrovascular stroma (green arrow); it was consistent with fibrovascular polyp (angiomatous). H&E, X100.

Macroscopically, the removed mass was a solitary, homogenous mass with a smooth skin surface, having dimensions of 35 × 15 × 10 cm and weighing 850 g, as shown in Fig. (3). The sample was subjected to histopathological analysis.

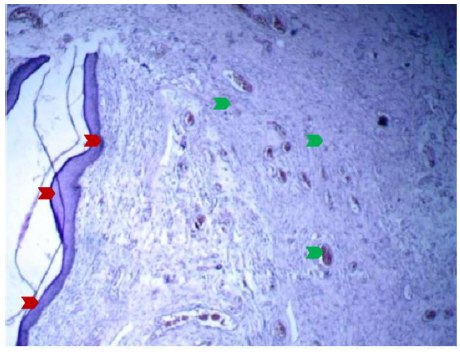

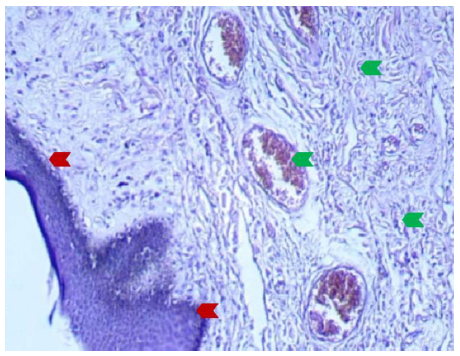

Under microscopic examination, the sections revealed benign squamous epithelium tissue covering the cystic wall, made of fibrous tissue with blood-filled blood vessels of various sizes. These vessels were lined by benign endothelial cells and accompanied by chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in certain areas. The observation indicated the presence of a fibroepithelial (fibrovascular) polyp, as depicted in Figs. (4 and 5). No cancerous cells or abnormal cells were detected.

Microphotograph showing benign-looking squamous epithelium (red arrow) with underlying fibrovascular stroma (green arrow); it was consistent with fibrovascular polyp (angiomatous). H&E, X200.

3. DISCUSSION

A giant fibroepithelial polyp is an uncommon vulvar tumor that arises from the mesenchyme. Although it is noncancerous, it mimics a malignant tumor. GFEPs reported in the literature in the last decade are summarized in Table 1.

In the earlier works, these GFEP tumours have been predominantly seen in the labia majora, vulva, and perineum. This can be attributed to hormonal sensitivity in these areas. The subepithelial stroma in the mentioned areas exhibits sensitivity to estrogen and progesterone, promoting the development and growth of these polyps. Many are indeed seen among reproductive-age women, further supporting this theory.

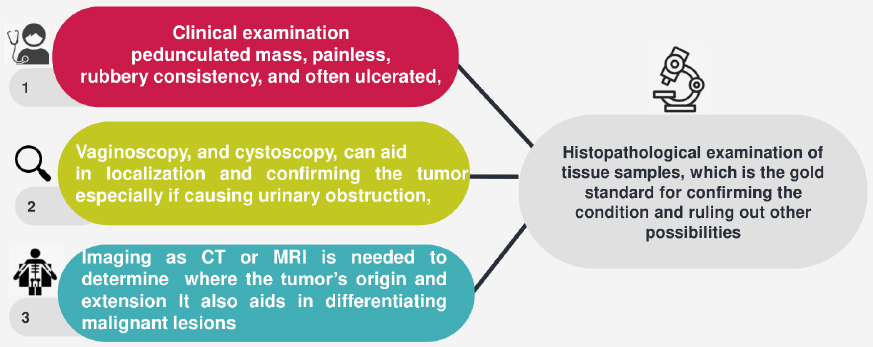

Another probable cause is that the vulvar area experiences friction and irritation. These mechanical stimulations may trigger the formation and expansion of these polyps in these anatomical sites. Characteristically, FEPs have a pedunculated nature, rubbery consistency, and often ulcerated surfaces, supporting the diagnosis. Vulvoscopy and biopsy play a crucial role in differentiating GFEPs from other vulvar lesions, particularly those of malignant potential [28]. Moreover, endoscopy has been reported to be useful in differentiating FEPs originating in the bladder and manifesting as hematuria [29].

The diagnosis of GFEPs is performed by histopathological examination of tissue samples, which is the gold standard for confirming the condition and ruling out other possibilities [30].

An accurate diagnosis usually requires further investigation; imaging modalities, such as CT or MRI, are sometimes employed for GFEPs to determine where the tumor originated and where it extends by looking at its blood supply and circulation, preferably pre-operatively. In addition, they help exclude other differential diagnoses, particularly those of malignant nature. Kato et al. highlighted that the identification of adipose tissue on MRI is a distinct observation that indicates FEPs [31]. Additionally, Yoo et al. declared observing adipose cell accumulation in close proximity to the stalk of FEPs, indicating MRI as beneficial in identifying fat [24]. Fig. (6) summarizes the diagnostic steps involved in detecting FEPs.

Some of the differential diagnoses associated with GFEPs of the vulva are presented as follows:

3.1. Condylomata Acuminata

It tends to be smaller in size, has usually multiple lesions, and indicates positive HPV testing.

3.3. Vulvar Sarcoma

It tends to grow faster with an irregular border and deeper involvement.

Other less common diagnoses include squamous cell carcinoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, granular cell tumors, neurofibromas, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and leiomyomas [14, 32, 33].

At the moment, the predisposing factors for GFEPs are not entirely understood. Unraveling the pathogenesis and etiology is critical for a comprehensive understanding of GFEPs. Certain hypotheses posit hormonal influences. Estrogen and progesterone fluctuations during pregnancy, hormone replacement therapy, and the use of combined birth control pills have been recognized to stimulate the growth of GFEPs’ epithelium, which has been proven to be responsive to hormones. Moreover, there are reports of tumor size reduction after pregnancy. Hormonal theory might explain why the majority of cases occur during the reproductive years [12, 24, 34-36].

Flow chart for diagnosing FEPs.

Some scholars have linked hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity as metabolic disorders with GFEPs [37].

Additionally, FEPs have been associated with people suffering from chronic inflammatory conditions, including Crohn's disease, psoriasis, and inherited lymphedema. Preliminary research indicates that their development may have a genetic component. Still, further research is needed [38-40].

The main approach to the treatment of GFEPs is surgical excision. Methods vary from basic excision to sequential excision for bigger polyps. It may be appropriate to pursue minimally invasive methods, such as laser ablation or electrocautery, for smaller lesions [16].

Surgical procedures involving extensive tissue removal may result in delayed wound healing, the formation of scars, and susceptibility to infections. Lymphedema manifestation entails the continuous utilization of compression garments and lymphedema treatment [21], [41]. A meticulous implementation of surgical methods, perioperative treatment, and the provision of suitable postoperative care for lymphedema are supposed to reduce these risks.

It is worth mentioning that GFEPs in pregnancy may impose therapeutic challenges, as they tend to grow rapidly and may bleed. Smet et al. [22] reported a case that presented in term pregnancy with a bleeding attack that called for an urgent surgical intervention to remove GFEPs of 15×11×4 cm and secure hemostasis. In order not to compromise the site of surgery, the decision was to deliver the baby via C-section.

It is important to remember that GFEPs can adversely impact the quality of life of the individual. The patient endures prolonged pain with the possibility of scarring and recurrence after the surgery, which can also have a negative effect on general well-being and sexual health. The presence of anxiety and depression linked to the initial diagnosis and its sequelae might persist even after the surgery. For that reason, it is crucial to pursue effective therapies for psychological components and provide emotional assistance to the patient [27, 42-45].

Although surgical excision is usually effective in treating GFEPs, a small number of cases may experience a recurrence, especially in cases with incomplete resection. Malignant transformation, although extremely rare, should still be considered. Regular post-treatment check-ups are essential for evaluating the possibility of recurrence and resolving any potential problems or malignant changes [13].

The heterogeneity of GFEP sizes and locations makes their identification challenging. It is still not clear why, in some cases, hormones are blamed for fast polyp growth, as in adolescence and pregnancy, while in other cases, the mass grows slowly for a while and then grows quickly for no clear reason [12].

To the best of our knowledge, the largest vulval GFEP reported has been of 42 cm [7]. The current case is the second-largest size ever reported in the literature.

Most of the published studies have been retrospective and case reports, including small numbers, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Investigating GFEPs’ pathogenesis, prognosis, long-term outcomes, and quality-of-life considerations can help develop a thorough understanding of these fascinating tumors. Continued study is necessary to improve management techniques and deepen our comprehension of these distinct vulvar tumors.

CONCLUSION

Giant fibrovascular vulvar polyps in young females are rare, but significant benign growths that require careful clinical evaluation and management. These polyps typically present as large, often painless masses in the vulvar region and can be associated with mechanical stress or hormonal influences. Early diagnosis is crucial for appropriate intervention, which may involve surgical excision to prevent complications, such as discomfort, ulceration, or potential malignancy. While most cases are benign, understanding their pathophysiology and considering differential diagnoses, such as tumors or infections, are important in establishing the correct treatment plan. Further research is needed to explore the underlying causes, risk factors, and long-term outcomes of these uncommon yet impactful lesions in young women.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed equally to the manuscript and agreed to the submission of the final version.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| FEPs | = Fibroepitheial Polyps |

| Cm | = Centimeter |

| GEPs | = Giant Fibroepitheial Polyps |

| MRI | = Magnatic Resonance Imaging |

| HPV | = Human Papilloma Virus |

| CT | = Compound Tomography |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study obtained ethical approval from the ethics committee of Mustansiriyah University, Baghdad, Iraq (ref. no. MOG 37; dated 6/2024).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

An informed consent was obtained from the patient before performing the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the College of Medicine, Al-Musnasiriyah University, Iraq.