All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Nanobiomaterials for Skin Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: From Mechanistic Understanding to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Cell- and tissue-based therapy, as the main subfields of regenerative medicine, are critical interdisciplinary fields that are anticipated to constitute a significant portion of future medicine. To design and develop more effective cell- and tissue-based therapies for a diverse array of medical uses, particularly in the fields of skin tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, nanotechnology, biomaterial sciences, stem cell biology, and biomedical engineering, researchers are collaborating. Recently, the emergence of nanotechnology has revolutionized the landscape of skin tissue engineering and regenerative medicine by enabling the development of advanced nanobiomaterials and nanostructures with unparalleled functional and engineering properties. This narrative review aims to investigate the various applications of nanotechnology-based knowledge in cell- and tissue-based therapies for skin regeneration and dermatological practices. This study addresses the effects of nanotechnology-based approaches on biological responses, cell behavior, tissue integration, and the functional recovery of biological structures. Furthermore, the study highlights the promise of combining nanobiomaterials with cell engineering approaches to advance therapeutic outcomes in skin repair. According to a literature review, nanobiomaterials that are both effective and supportive can help produce structures resembling natural biological ones, alter the extracellular matrix, and direct stem cell fates. Nevertheless, the aim of the study is to encourage additional research and innovation, thereby establishing the foundation for the development of next-generation regenerative therapies for skin conditions and dermatology.

1. INTRODUCTION

The skin is one of the most important and vital structures in the body, making up about 16% of an adult's total body weight. Any damage to the skin's structure can have catastrophic effects, including injury, recuperation, long-term problems, and even mortality [1]. Skin is the most important link between a multicellular organism and its environment. It is made up of many layers, including the epidermis (which protects against water), the dermis (which gives the skin strength and elasticity), and the hypodermis (which lies beneath the dermis) [2, 3]. The skin is important for more than just its physical makeup. It also helps keep the body at a functional temperature, prevents dehydration, and protects against several outside hazards, such as mechanical, chemical, thermal, and pathogenic agents, and UV exposure [4]. However, constant contact makes skin tissue prone to harm, which can lead to serious medical problems, from hospitalization to life-threatening infections [5]. Traditional therapeutic approaches, including autologous skin grafts, have considerable clinical constraints, such as donor site mortality, limited accessibility for severe burns, and often suboptimal cosmetic and functional outcomes [6]. Moreover, allogeneic transplantation carries a risk of immunological failure. Consequently, the pressing necessity to completely regenerate functioning skin tissue has driven progress in skin Tissue Engineering (TE) and Regenerative Medicine (RM) [7-9]. This multidisciplinary field integrates medicine, biology, materials science, and engineering principles to create effective biological replacements designed to restore, preserve, or augment the performance of damaged tissues, thereby proving their significance in the management of severe dermatological conditions [8, 9]. The “tissue engineering triad,” which includes cells, biologically active signaling molecules, and a supportive, flexible scaffold, is the cornerstone of TE [10, 11]. The scaffold is likely the most essential element, as it must physically and physiologically replicate the natural Extracellular Matrix (ECM). However, the ECM is a dynamic network that offers mechanical durability, biochemical signals, and a structural framework crucial for governing cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and tissue remodeling [12, 13]. The goal of contemporary TE is to obtain superior results through the utilization of cutting-edge nanotechnology-based approaches [14]. Techniques that enable the accurate manufacturing of materials at the nanoscale (1–100 nm) can be used to create scaffolds that closely mimic the fibrous architecture, high porosity, and surface-area-to-volume ratio of the native extracellular matrix (ECM) [15]. This results in a significant improvement in the communication between cells and the matrix, as well as the possibility of regeneration [16, 17]. Therefore, in addition to well-mimicked scaffold fabrication, nanotechnology-based knowledge can improve stem cell research by enhancing their survival and functionality. However, different cell types from different sources can be used for TE and RG purposes. Stem cells, including embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells, as well as differentiated cells, such as keratinocytes and fibroblasts, are high-potency cell sources available for use in skin TE and RM [7, 18-20]. This review paper comprehensively reviews and critically evaluates recent advancements in nanotechnology-driven approaches for skin TE. Recent advancements in biomimetic nanostructured scaffolds are examined, the most efficient nanofabrication methods (including electrospinning and 3D bioprinting) are outlined, and the use of diverse nanomaterials (natural, synthetic, and hybrid) in enhancing wound healing and implementing anti-aging strategies is analyzed. The existing limitations and future prospects for the therapeutic implementation of these revolutionary nano-engineered skin substitutes are emphasized.

2. SEARCH STRATEGY

A non-systematic search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to establish the foundational basis for this narrative review. The terms used were “nanobiomaterials,” “nanomaterials,” “skin tissue engineering,” “regenerative medicine,” “nanofibers,” “electrospinning,” “3D bioprinting,” “wound healing,” and “nanoparticles.” The sources were chosen because they were relevant to the use of nanotechnology in skin regeneration, focusing on recent developments and the medical uses of the technology.

3. NANOTECHNOLOGY IN SKIN REGENERATIVE MEDICINE: PRINCIPLES AND BIOMIMICRY

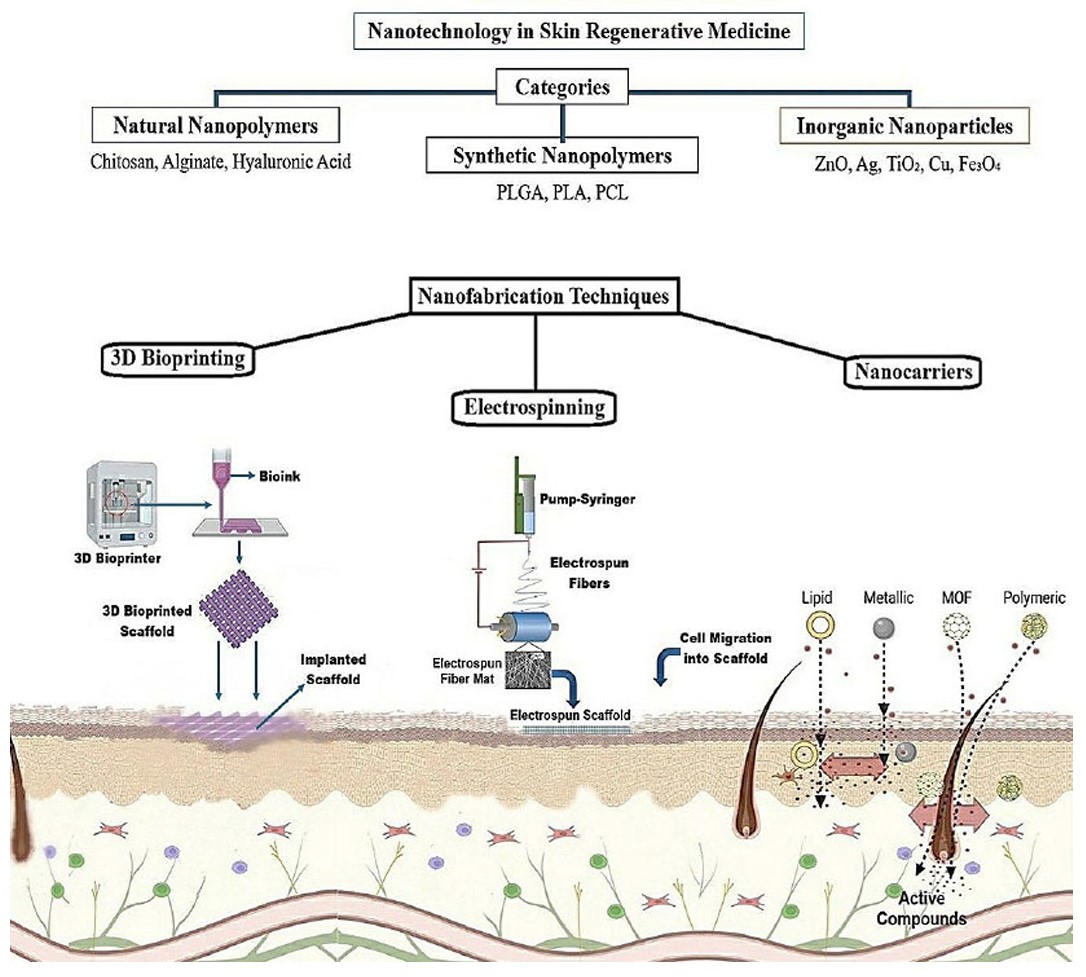

Nanotechnology is an extensive area that includes many areas of science, from molecular biology to research on improved materials. The main goal is to create, manipulate, and control materials at the nanoscale with great precision to achieve better or new functions [21]. The effective integration of nanotechnology has radically altered RM, particularly in TE and pharmaceutical delivery systems [22]. The overall benefit has mostly come from combining nanoscale materials with multifunctional polymers to make pharmaceutical designs and target tissues far more effective and biocompatible [22]. All native tissues exhibit unique structural attributes at the nanoscale, and it has been conclusively established that the integration of nano-topographies onto biomaterial surfaces significantly enhances the functionality, affinity, and accessibility of various cell types. People often call the materials made this way “bio-nanomaterials” [23]. Nanotechnology expansion efforts generally focus on two strategic methodologies: modifying the chemical structure of a material or altering its physical characteristics, including visual shape, an enhanced surface area-to-volume ratio, or mechanical characteristics such as improved tensile strength, hardness, and Young's modulus [24]. These unique characteristics allow for the exact modification of biomaterials by changing chemical and biological factors to improve positive cellular connections and physical signaling capabilities [21]. Although the skin is the largest organ and serves as the principal physiological protection, it is perpetually subjected to injury [25]. Nanotechnology facilitates the fabrication of nanomaterials and nanoconstructs, which are pivotal in developing an effective therapy method based on TE and RM (Fig. 1). Nanoscience thus offers a vital technical conduit to enhance and expedite advancements in skin regeneration, wound healing, and anti-aging strategies.

Applications of nanotechnology in skin RM. (A) Compounds used in skin regeneration are categorized based on their origin into natural nanostructured polymers, synthetic nanostructured polymers, and inorganic nanoparticles, which can function as scaffolds or nanocarriers. (B) Nanomaterials enhance skin regeneration through various approaches, including the use of implantable scaffolds fabricated by 3D bioprinting or electrospinning, as well as nanocarriers designed to deliver active therapeutic agents to injured skin. Utilization of nanotechnology in skin regenerative medicine. Substances employed in skin regeneration are classified by their origin into natural nanostructured polymers, synthetic nanostructured polymers, and inorganic nanoparticles, which serve as scaffolds or nanocarriers. Nanomaterials facilitate skin regeneration using multiple methods, including implantable scaffolds created via 3D bioprinting or electrospinning and nanocarriers engineered to transport effective medicinal medicines to damaged skin.

4. ADVANCED NANOFABRICATION TECHNIQUES FOR SKIN SCAFFOLDS

Creative strategies are used to create advanced nanoscale scaffolds for imitating the natural ECM. Electrospinning, self-assembling, 3D bioprinting, and cell-imprinting are the main nanostructured platform production methods [26]. Microfluidics and 'organ-on-chips' models provide dynamic, high-throughput assessment of synthetic skin replacements, providing a more precise physiological backdrop for preclinical evaluation [27]. Table 1 summarizes the main nanofabrication technologies used to produce biomimetic scaffolds for skin TE, along with their pros and cons.

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Applications in Skin TE | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning | High-voltage ejection of polymer jet to form nanofibers (100 nm–microns) | Affordable, scalable; high porosity, oxygen permeability; antimicrobial potential | Sensitive to parameters (e.g., voltage, humidity); 2D sheets dominant | Wound dressings; ECM-mimicking fibers | [28] |

| Self-Assembly | Spontaneous molecular coordination via non-covalent interactions (e.g., van der Waals, hydrophobic) | Biomimetic; forms nanotubes/fibers; enhances angiogenesis (e.g., with PAs) | Weak interactions; pH/ionic sensitivity; scalability challenges | Drug/gene delivery; nanofibrous hydrogels | [26, 29] |

| 3D Bioprinting | Additive deposition of bio-inks (cells, hydrogels) via CAD; subtypes: inkjet, microextrusion, SLA | Precise layering; high resolution; in vivo printing possible | Viscosity/cell viability issues; complex for multi-component tissues | Full-thickness skin models; porous scaffolds | [8, 30] |

| Cell-Imprinting | Topographical guidance mimicking ECM morphology for stem cell behavior | Optimized microenvironment; promotes adhesion/migration | Limited to specific cell types; fabrication complexity | ADSC reshaping for keratinocyte cues | [31, 32] |

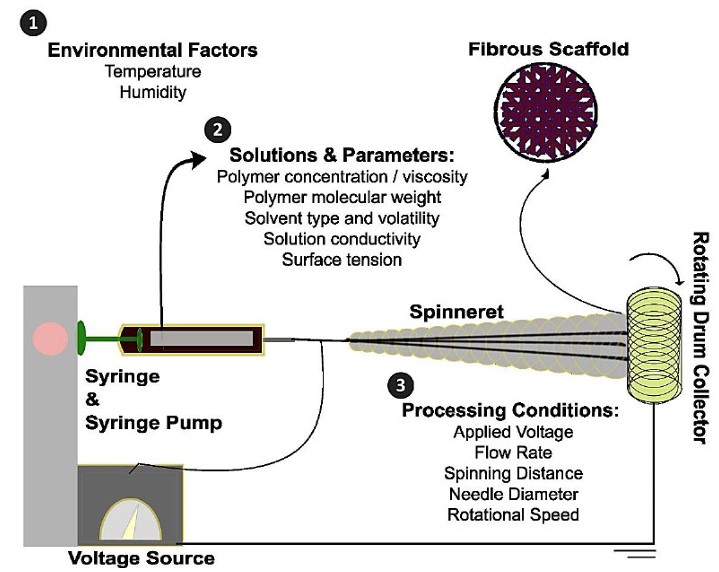

4.1. Electrospinning

Electrospinning produces polymeric nanofibers easily, adaptably, and cheaply [15, 33]. This method easily creates densely linked networks of fibers ranging from 100 nm to microns wide, which may be positioned arbitrarily [34]. Several parameters affect electrospinning based on the object's desired features (Fig. 2). A high-voltage electrical current is applied to a polymer solution to eject an electrostatic polymer jet from a syringe. This jet crosses a gap and deposits fibers with interconnected pores onto a collector, thereby improving the scaffold's structural properties [35]. Operational parameters, such as polymer molecular weight and concentration, solvent quality, applied electrical voltage, polymer flow rate, collector-syringe distance, and environmental conditions (temperature and humidity), greatly affect fiber morphology [28]. Electrospun nanofibers are widely used as wound dressings due to their moderate uptake, increased oxygen permeability, improved nutrient and metabolite exchange, and ability to transport and release antimicrobial agents [36]. Coaxial or emulsion electrospinning produces core-shell fibers that encapsulate and regulate the release of sensitive therapeutic substances like growth factors or genetic material [37]. Alginate, hyaluronic acid, and collagen are mixed with synthetic polymers like Polycaprolactone (PCL), Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and polyethylene terephthalate to make fibers that combine the mechanical strength of synthetic materials with the biological signals of natural proteins [38]. Electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for skin TE and wound healing use PCL, PVA, PHBV, PEO, CS, collagen, and Polyurethane (PU) as their main polymers [39]. Thus, nanofibrous constructs in skin TE and RM have potential for positive properties.

Schematic illustration of the electrospinning process and summary of key variables influencing the fabrication of nanofibrous scaffolds.

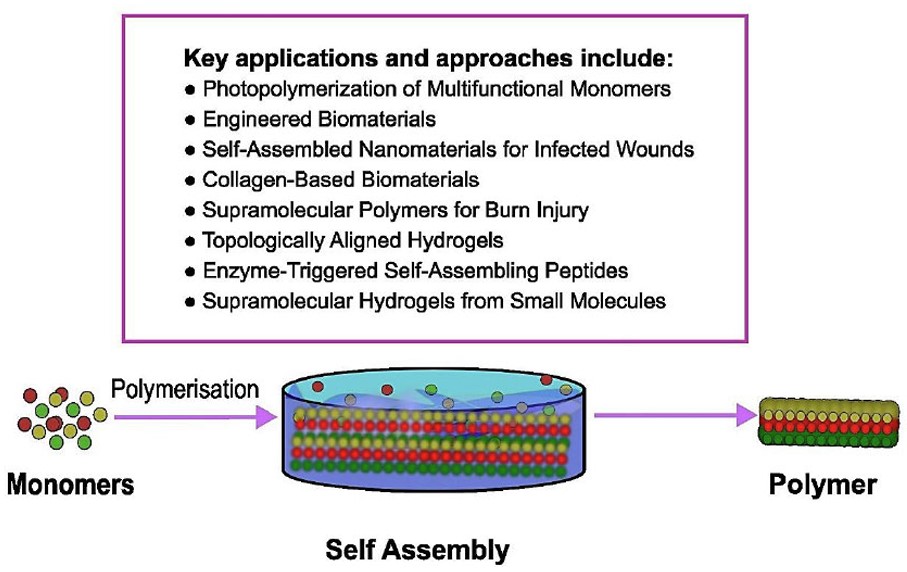

4.2. Self-assembly

Self-assembly is another effective skin TE and RM approach. Self-assembly creates highly structured supramolecular structures by spontaneously organizing molecules through non-covalent interactions (Fig. 3) [29]. Innovative nanomolecular devices that interact with living cells and modulate their biological processes are created using this technology [40]. Nanotubes, nanofibers, and specialized carriers can be self-assembled [41]. This approach improves intracellular communication using biocompatible, biodegradable, and bioactive nanoparticles and sophisticated hydrogels [42]. Poor contacts like Van der Waals, hydrophobic, and electrostatic forces control self-assembly [43]. Bipolar peptides, especially Peptide Amphiphiles (PAs), are a key self-assembly method in soft TE because they interact with ECM-derived peptides that influence cellular destiny and differentiation [42]. Ionic solutions or pH changes can influence nanofiber production. PAs can form complex chains and boost angiogenesis, which is necessary for dense tissue regeneration, when combined with hyaluronic acid or heparin [26]. Thus, micelles and nanocomposite hydrogels are essential for targeted drug and gene delivery, thereby maximizing the therapeutic efficacy of encapsulated agents such as stem cells, growth factors, and antibiotics for soft tissue injuries and complex cutaneous wounds [44, 45].

Schematic illustration of the self-assembly process and summary of key applications influencing its use in dermatology and skin disorder treatment.

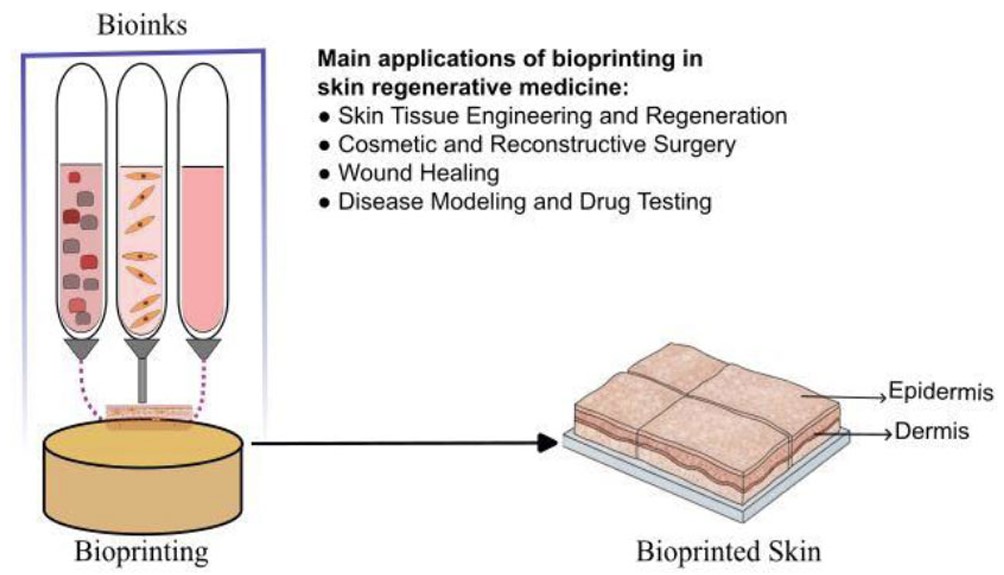

4.3. Skin 3D Bioprinting

Skin three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting uses Computer-Aided Design (CAD) to precisely deposit bio-ink constituents like hydrogels, living cells, and extracellular matrix materials into a three-dimensional configuration [30]. Its potential for future application in TE and RM is confirmed by numerous studies, which are based on its substantial advantages [34]. Its use is also tested in cutaneous TE and RM (Fig. 4). Inkjet, microextrusion, and laser-assisted bioprinting each have different material viscosity tolerance and cell survival [46]. In vivo bioprinting deposits cells and biomaterials onto wounds and burns to regenerate functional skin [8]. Drug development and accurate in vitro tissue models require this technology [47]. Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA) bioprinting is used to print complex, multi-component tissues at high resolution. SLA's strengths include high resolution, cell viability, and complicated geometric shapes, such as high-precision tissue scaffolds with tailored porosity structures [30].

Schematic illustration of 3D bioprinting and summary of key applications in skin tissue engineering (TE) and regenerative medicine (RM).

4.4. Cell-imprinted Substrates

Stem cells and a proper microenvironment allow regenerative tissues like skin to regenerate [31]. Cell-imprinted substrates create an optimized, topographically directed 3D surface that closely resembles the natural ECM [32]. This approach uses contact guiding, where substrate properties affect cell behavior. Skin regeneration uses stem cells, specifically ADSCs from adipose tissue. The imprinted substrate can morphologically and biochemically change ADSCs to mimic the natural skin microenvironment's keratinocyte, elastin, collagen, and soluble factor configurations [48].

5. NANOMATERIALS FOR SKIN: CLASSIFICATION AND FUNCTION

The effectiveness of a nanostructured scaffold depends on the chemical and natural features of the biomaterials it is made of. Origin arranges materials into categories, which changes how strong they are, how quickly they break down, and how they interact with living beings [8, 49]. Skin TE requires a nanomaterial that promotes cellular contact, proliferation, and division while preserving mechanical homeostasis in vivo. Nanocapsules, NPs, Nanofibers (NFs), and nanosheets [50], are widely employed on account of their size-dependent characteristics [51]. Nanofibers generate a porous ECM-like membrane with a high surface area-to-volume ratio. Chemical functionalization and cell-matrix interactions are improved by this trait [51, 52]. The ideal scaffold design promotes wound healing by promoting nutrient exchange and cell migration with a target pore size of 80-100 µm [53]. Table 2 classifies nanomaterials for skin scaffolds by their characteristics, TE roles, and necessary changes to overcome mechanical instability and cytotoxicity.

| Category | Examples | Key Properties | Functional Role in Skin TE | Challenges/Modifications Needed | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Collagen, gelatin, elastin, fibrin; Chitosan, HA, alginate, bacterial cellulose | Biocompatible, bioactive; low immunogenicity; antimicrobial/hemostatic (chitosan); shear-thinning (HA) | ECM mimicry; cell adhesion/proliferation; wound remodeling; growth factor retention | Poor mechanical strength; rapid enzymatic degradation; requires cross-linking | [45, 49-55] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PCL, PLGA, PLA; Polyurethane (PU); PVA | Tunable degradation; high elasticity (PCL/PU); reproducible mechanics | Structural support; controlled drug release; skin-like compliance (PU for dermal scaffolds) | Hydrophobicity; lack of inherent bioactivity; needs blending/surface modification | [34, 47, 56, 57] |

| Inorganic NPs | ZnO, Ag, TiO2, Cu, Fe3O4; Graphene Oxide (GO) | Antimicrobial/antioxidant; high surface area; angiogenic (ZnO via MAPK/Akt); conductive (GO) | Infection control; angiogenesis promotion; ROS scavenging; electroactive signaling | Potential cytotoxicity; NP aggregation; requires controlled dosing/integration | [58-63] |

| Hybrid/Blends | Collagen-PCL; Chitosan-PVA; Gelatin-HA nanocomposites; Curcumin-PCL/PVA | Combines bioactivity/mechanics; enhanced hydrophilicity; sustained release | Multifunctional scaffolds; VEGF/drug delivery; balanced durability and signaling | Ratio optimization for biocompatibility; stability in vivo; fabrication complexity | [52, 64] |

5.1. Natural and Bioactive Nanostructured Polymers

The biocompatibility, minimal immunogenicity, and inherent bioactivity of natural polymers make them valuable in skin TE. These features allow them to replicate the natural ECM's structure and signaling [54]. Many polymers have binding sites and signaling patterns that promote cell adhesion, migration, and growth factor retention [55]. ECM-derived parts: Bio-signals from collagen, gelatin, elastin, and fibrin help cells adhere, proliferate, and differentiate [50]. Denatured collagen and gelatin have enhanced solubility but require chemical cross-linking to increase mechanical strength and slow enzymatic breakdown [56]. Chitosan, HA, alginate, and bacterial cellulose are common polysaccharides in TE [52, 57]. Chitosan's intrinsic antibacterial, hemostatic, and anti-inflammatory characteristics make it ideal for wound dressings [58]. Polysaccharide nanofibers enhance tissue remodeling and absorption [59]. HA-based hydrogels are popular injectable bioinks because they shear-thin and control fibroblast behavior [60].

5.2. Synthetic and Mechanically Tunable Nanostructured Polymers

Mechanical tunability, exact repeatability, and highly controllable degradation profiles are improved by synthetic polymers, overcoming natural materials' mechanical strength constraints [38]. They are typically engineered to offer the necessary temporary mechanical support during the regeneration phase. Biodegradable polyesters, such as PCL, PLGA, and Poly (Lactic Acid) (PLA), are among the most widely used polyesters [52]. PCL is ideal for long-term applications due to its high elasticity and degradation duration. PLGA allows precise control of the degradation rate, which is important for controlled medication administration [61]. These materials need their surfaces modified or mixed with natural polymers because they are hydrophobic and lack biological activity. People like PU because it is very flexible and has mechanical properties that are similar to human skin. Due to this, PU is necessary for elastic, high-compliance dermal scaffolds [62].

5.3. Inorganic and Functional Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles (NPs) possess a minimum diameter of one nanometer [63]. Nanostructures are interesting for tissue regeneration, monitoring, and diagnosis because of their distinctive chemical and physical characteristics and quantum size effects [63]. To have antibacterial, angiogenic, and antioxidant properties, the polymeric scaffold backbone required inorganic nanoparticles and composite components [64]. Antimicrobial and antioxidant substances: Scaffold architectures include a number of NPs, such as Zinc Oxide (ZnO), Silver (Ag), Titanium Dioxide (TiO2), Copper (Cu), and Iron Oxide (Fe3O4) [65]. Silver or nanosilver and iron oxide NPs in fibers form bespoke dressings with powerful antioxidant and antibacterial capabilities that inhibit Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [66].

5.4. Angiogenic and Conductive Promoters

Some inorganic nanomaterials directly affect tissue healing [67]. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnONPs) increase endothelial cell migration and blood vessel formation via MAPK/Akt/eNOS [68]. Graphene Oxide (GO) and other carbon-based nanomaterials increase scaffold electrical conductivity, which stimulates electrically sensitive biological signaling pathways [69]. Innovative hybrid nanocomposites, including Type I collagen/TiO2-PVP composites, combine natural polymers' biological qualities with synthetic or inorganic components' mechanical strength [57]. This combination strikes a balance between mechanical endurance and cellular communication endurance. Bioactive compounds, such as curcumin, can destroy bacteria, pus, and debris in the wound bed when applied to composite scaffolds such as Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) or Polycaprolactone (PCL). This speeds up the disinfection and rehabilitation of the wound [70].

6. CLINICAL AND THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS OF NANO-ENGINEERED SCAFFOLDS

The primary goal of developing nanostructured scaffolds is to convert their improved biomimetic and functional properties into real clinical benefits for skin repair and regeneration. Nanotechnology has shown significant effectiveness in various therapeutic areas, particularly in the intricate management of chronic wounds and advanced aesthetic anti-aging treatments [71].

6.1. Accelerated Wound Healing

Trauma, burns, chronic problems (such as diabetic or venous ulcers), or disorders that damage the skin's integrity make treatment very difficult [51]. The goal of skin engineering and regeneration therapy is to make structures that look and work like the ECM in the dermis and epidermis [72]. This method gives the right biological signals to let native cells grow, move, and change in a regulated way [50]. However, due to the intricate physiopathological characteristics of the wounds, particularly in the case of a chronic wound, additional therapeutic factors become significant. For example, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory drugs have a big effect on how chronic wounds heal [73]. Consequently, the ideal nanoconstruct can concurrently serve as a medication and cell delivery mechanism. Nonetheless, data underscores that mesenchymal stem cells exhibit anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties in both in vitro and in vivo settings [74-77]. In contrast, infection and antibiotic use are crucial in the management of wounds, especially chronic ones. Consequently, in the pursuit of an optimal nanoconstruct for wound healing, it is essential to evaluate the requisite characteristics for the delivery of portions, such as anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and organic substances with comparable effects, alongside the simultaneous administration of cells such as mesenchymal stem cells and keratinocytes [20, 75].

6.1.1. The Nanotechnology Solutions in Wound Care

Nanotechnology-based therapies, including nanoparticles and nanofibrous scaffolds, can significantly enhance wound healing. These sophisticated nano-based solutions have shown promising results in promoting tissue regeneration and mitigating inflammation [78, 79]. They can also help with wound healing by reducing scarring and speeding up the process. Table 3 shows how nano-engineered scaffolds can be used for wound healing and anti-aging treatments, as well as how they work and what therapeutic benefits they have.

| Application Area | Key Mechanisms | Nano-Engineered Examples | Outcomes/Benefits | Clinical Challenges | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound Healing | ECM mimicry (80–100 μm pores); sustained growth factor release (VEGF/PDGF); antimicrobial action | VEGF-loaded chitosan/PEO NFs; ZnO-PCL fibers; Curcumin-collagen composites | Accelerated closure/re-epithelialization; enhanced angiogenesis; reduced infection | Scalability; in vivo stability; mechanical matching to host tissue | [50, 74, 80] |

| Anti-Infective Therapy | ROS disruption/ion release (Ag+, Zn2+); anti-inflammatory (TGF-β modulation) | Ag NPs in gelatin-PVA mats; Fe3O4-PCL-gelatin membranes | Gram+/− bacterial inhibition; inflammation reduction; non-dehydrating disinfection | Resistance emergence; NP toxicity dosing; aggregation | [81-83] |

| Anti-Aging | ROS scavenging; collagen/elastin remodeling; nanocarrier penetration (liposomes/NLCs) | Bioflavonoid nanocrystals; Au NPs-alpha-lipoic acid; Vitamin C/retinoid NLCs | Wrinkle reduction; fibroblast proliferation; dermal thickening/antioxidant effects | UV/extrinsic aging efficacy; deep penetration; cytotoxicity | [84, 85] |

| Hybrid Scaffolds for Burns | Angiogenesis (CeO2); scarless healing; stimulus-responsive release/oxygen generation | ZnO-Curcumin collagen hybrids; Ge/SA/CNC scaffolds | Scar-free remodeling; improved absorption/mechanics; neovascularization | Donor morbidity; vascular delays; smart system accuracy | [86, 87] |

Nano-engineered scaffolds offer a superior therapeutic platform compared to traditional grafts [80]. Their effectiveness arises from several essential mechanisms:

6.1.1.1. ECM Mimicry and Cellular Response

Scaffolds engineered with precise mechanical characteristics and ideal pore dimensions (80–100 μm) provide effective cell adhesion, proliferation, and infiltration, essential for skin regeneration [88]. Three-dimensional electrospun nanofibers improve cell penetration and growth, which are important for repairing deep tissue [89]. To reduce negative reactions and improve cellular function, the scaffold's mechanical properties (such as strength, modulus, and viscoelastic creep) must also be carefully matched to the host tissue [90].

6.1.1.2. Particular Delivery of Therapies

Nanomaterials are employed as sustained-release systems to enhance rehabilitation effects [91], which encompass:

- Encapsulation of Growth Factors: For instance, VEGF-loaded chitosan/PEO nanofibers or PDGF-BB-loaded PLGA nanoparticles embedded in nanofibers are developed for the sustained release of growth factors, leading to prolonged therapeutic effects [92].

- Active Compounds: Curcumin, a bioactive agent, may be incorporated to assist in the removal of germs, pus, and debris from the wound bed [93]. Moreover, arginine-infused scaffolds have demonstrated beneficial effects on cellular migration and proliferation [94].

- Gene and MicroRNA Delivery: Sophisticated nanocarriers like liposomes and dendrimers safeguard delicate nucleic acids (e.g., antisense oligonucleotides) from enzymatic degradation, facilitating their controlled release to regulate gene expression in the wound milieu [95].

6.1.1.3. Antimicrobial Efficacy

Nanoscaffolds possess intrinsic antibacterial and anti-inflammatory characteristics, typically realized by the integration of nanoparticles such as silver or zinc oxide. This facilitates efficient cleaning and the control of chronic inflammation without desiccating the wound bed [81]. ZnO nanoparticles (ZnONPs) incorporated into polymeric fibers markedly enhance cell adhesion and fibroblast proliferation, thereby expediting the wound-healing process [82].

Enhanced Functionality: Employing materials that generate oxygen, such as sodium percarbonate or calcium peroxide, and sending them through microchannels, is among the new ideas. These materials have shown significant benefits for reepithelialization, neovascularization, and collagen remodeling [96]. The latest innovative development entails the creation of intelligent stimulus-responsive nanosystems that allow wound dressings to identify infection biomarkers and accurately deliver the necessary medicinal drug as needed, advancing closer to genuine individualized wound care [97].

6.2. Targeted Drug and Gene Delivery Systems

Nanomaterials have changed how drugs are delivered in dermatology and wound care by making it possible to release active substances in a targeted and controlled way. This advancement tackles the issues of inadequate solubility and systemic toxicity frequently linked with traditional therapies. Nanocarrier Design: New types of nanocarriers, such as liposomes, nanoemulsions, Solid Lipid Nanocarriers (SLNs), and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) [98], make it easier for medicinal chemicals to cross the skin and enter the body. For instance, intricate systems like gelatin/hyaluronic acid scaffolds that utilize atorvastatin-loaded NLCs demonstrate potential for cohesive drug delivery within regenerative scaffolds [99]. This unique nanodelivery technology is especially helpful because it makes poorly water-soluble medications more bioavailable and prevents bioactive compounds from breaking down in situ due to enzymes or changes in pH [21].

Improving cell treatment: NPs are being used more and more with cell treatment to help cells stay alive, survive, and secrete angiogenic factors in a specific area [100]. NPs and cell treatment are often combined to enhance the release of angiogenic factors [100]. For example, CeO2-NPs added to polymeric scaffolds can act as beneficial angiogenic structures, accelerating blood vessel growth in TE [101]. Gold nanoparticles, for example, can carry chemicals like alpha-lipoic acid that help control inflammation and the growth of new blood vessels [102].

6.3. Anti-aging Methods and Dermal Regeneration

Intrinsic and extrinsic factors both cause skin aging, which is characterized by decreased collagen levels and reduced interstitial water content [8]. A major part of this procedure is UV light, which makes damaging Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [84]. Nanomaterials are very important for developing new anti-aging methods, as they have unique surface chemistry and are highly reactive.

1. Antioxidant Properties: Nanomaterials are effective at picking up ROS [103]. Nanocrystals derived from bioflavonoids, natural polyphenolic chemicals, can be synthesized using top-down or bottom-up approaches.

These nanocrystals are particularly effective at penetrating the epidermis and exhibit several pharmacological actions, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging effects [104].

2. ECM Support and Reconstruction: Nanofibrous structures give structural support and signaling signals that help the body make collagen and elastin again. This procedure is crucial for making the dermis thicker and making wrinkles less noticeable [105]. This application relies heavily on new nanocarriers, such as liposomes, nanoemulsions, and NLCs, which help deliver active anti-aging drugs deeper into the skin [8, 98].

3. Improved Delivery: Nanocarriers help cosmeceuticals like vitamin C and retinoids reach deeper into the skin by targeting them more effectively. This makes them much more effective than regular topical preparations [106]. Using these nanocarriers makes it easier for drugs to go into damaged or old skin layers while also lowering the risk of medication toxicity [107].

7. CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite substantial advances, numerous pivotal obstacles hinder the integration of these discoveries into widespread clinical applications:

- Complexity of Models: Current 3D in vitro models still have trouble adequately mimicking the skin's complex structure and different layers [51].

- Availability and Individualization: Making scaffolds that are very accurate for each patient, as well as the difficulties of increasing production for widespread clinical utilization, are major engineering issues [98].

- Directive Framework: There is an urgent need for clear and defined rules for complicated nanocomposites to make it easier for them to be used in clinical settings.

The future of skin regeneration medicine is moving toward smart nanosystems that respond to stimuli, which are commonly called “innovative dressings.” These high-tech gadgets will be able to keep an eye on the wound environment in real time, such as pH levels and infection indicators, and they will be capable of starting the exact release of medicines on their own. This is the next step in individualized and very effective skin rejuvenation and repair. Additionally, creating scaffolds that actively improve stem cell preservation, persistence, and differentiation in situ is a fantastic way to achieve full and functional skin regeneration.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

Nanotechnology has changed the field of skin regeneration medicine in a big way. This advancement addresses critical clinical challenges associated with traditional skin grafting, such as donor site morbidity and immunological rejection [6]. This study stresses that nano-engineered scaffolds are a big part of this change since they can look and work like the native ECM at the nanoscale. Electrospinning, 3D bioprinting, and self-assembly are all advanced nanofabrication methods that let you make scaffolds with excessive surface area-to-volume ratios, regulated porosity, and customizable mechanical properties [8, 108]. To make efficient regenerative constructs, it is important to use natural nanostructured polymers (like collagen and chitosan) for their natural bioactivity, synthetic polymers (like PCL and PLGA) for their mechanical flexibility, and inorganic nanoparticles (like AgNPs and ZnONPs) for their strong antimicrobial and angiogenic properties [109]. There are several clinical uses for these nano-engineered systems. They are better at speeding up wound healing because they improve cell adhesion, control inflammation, and deliver therapeutic substances (such as growth factors or antibiotics) over time [74, 110]. Nanocarriers are also becoming more essential in anti-aging treatments. They help transport antioxidants deep into the skin, where they can help repair damage caused by toxic substances and promote skin remodeling. Therefore, this new area needs further investigation, and multiple studies are already underway.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: A.G.: Conceived the study conception, designed and supervised the review, and all authors conducted the review and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| 3D | = Three-dimensional |

| ADSCs | = Stem cells derived from adipose tissue |

| Ag | = Silver |

| CAD | = Computer-aided design |

| CS | = Chitosan |

| Cu | = Copper |

| ECM | = Extracellular matrix |

| Fe₃O₄ | = Iron Oxide |

| GO | = Graphene Oxide |

| NFs | = Nanofibers |

| NLCs | = Nanostructured Lipid Carriers |

| NPs | = Nanoparticles |

| PAs | = Peptide Amphiphiles |

| PCL | = Polycaprolactone |

| PEO | = Polyethylene Oxide |

| PHBV | = Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| PLA | = Poly (lactic acid) |

| PLGA | = Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PU | = Polyurethane |

| PVA | = Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| RM | = Regenerative Medicine |

| ROS | = Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SLA | = Stereolithography Apparatus |

| SLNs | = Solid Lipid Nanocarriers |

| TE | = Tissue Engineering |

| TiO₂ | = Titanium Dioxide |

| ZnO | = Zinc Oxide |

| ZnONPs | = Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

AI DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used QuillBot for language editing, academic writing, and grammar improvement. After its use, the authors thoroughly reviewed, verified, and revised all AI-assisted content to ensure accuracy and originality. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and final content of the published article.