All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Pseudo-epitheliomatous Hyperplasia and Skin Infections

Abstract

Introduction

The histological pattern of pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) may be encountered in a large series of verruciform/crateriform skin lesions (VC) with or without central ulceration/crusting. Beside neoplastic and inflammatory processes, this clinico-histological pattern may be associated with an extensive range of infectious agents.

Materials and Methods

A literature search was performed to identify viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic mucocutaneous infections potentially presenting with a clinical/histological VC-PEH pattern.

Results

A VC-PEH pattern was reported in parasitic (n=5), viral (n=6), bacterial (n=10), and fungal (n=12) mucocutaneous infections. The infection-linked VC-PEH pattern was typically linked to longstanding mucocutaneous processes. The human papillomavirus (HPV) family, Epstein-Barr virus, poxvirus, and polyomavirus-linked VC-PEH patterns seem to act as direct triggers of keratinocytic hyperproliferation whereas the VC-PEH patterns observed during other viral, parasitic, bacterial and fungal infections probably represent a reactive pattern of the epidermis to chronic mucocutaneous infections. The VC-PEH pattern was also more frequently reported in immunocompromised compared to immunocompetent patients. The risk of the development of a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in chronic VC-PEH should not be overlooked.

Conclusion

In the event of longstanding, slowly progressing, isolated, or more profuse VC-PEH skin lesions, a thorough search for infectious agents should be considered, particularly in the immunocompromised patient.

1. INTRODUCTION

Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) represents a histological pattern with a heterogenous expression, including pseudo-epitheliomatous papillomatosis, carcino- matoid hyperplasia or verruciform hyperplasia [1-3]. PEH may present various degrees of papillomatosis, hyper- keratosis and acanthosis [1-3]. They are all characterized by a certain degree of hyperproliferation of epidermal keratinocytes.

The clinical manifestations of the histological PEH pattern are also variable, but all have in common a more or less verruciform/crateriform aspect (VC). VC-PEH lesions may present as single or multiple, small or large, sometimes confluent, and with or without central ulceration or crust formation [4].

The etiology of VC-PEH cutaneous lesions is also considerably varied, including neoplastic, inflammatory, and mechanical origins, as well as an important range of infectious causes.

Most skin infections usually present with a typical clinical manifestation [5]. However, on occasion, they may present as VC lesions that are more difficult to recognize on clinical grounds only and represent a histological challenge. Sometimes, sampling techniques do not gather enough material, are not performed deep enough, or are simply pauci-organism skin lesions. Histological sampling, especially by a punch biopsy, may only permit the patho- logical analysis of a small part of the lesion and may potentially lead to an erroneous diagnosis. An excisional biopsy should be recommended.

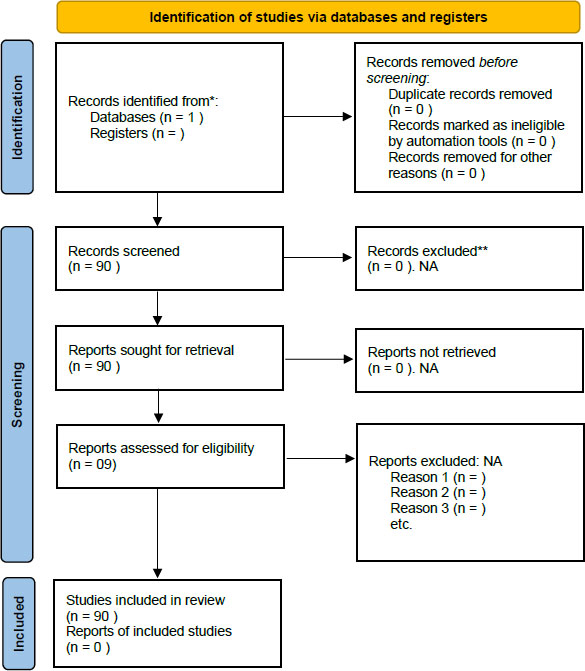

PRISMA flowchart of the study.

This comprehensive review presents the findings of a literature search on infectious agents that may, on occasion, present with a VC-PEH pattern. Furthermore, their histological presentation, potential pathomechanism, the patient’s comorbidities, the recommended diagnostic methods, and treatments are presented as described in the ad hoc publications.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A literature search was performed using the PUBMED database including the following search terms: pseudo- carcinomatous hyperplasia”, “epidermal hyperplasia”, “hyperkeratosis”, “pseudo-epitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia”, “verruciform”, “verruciform hyperplasia”, “wart-like”, “verrucous”, “acanthosis”, matched with “infection”, “viral”, “virus”, “bacterial”, “fungal”, “mycosis”, “fungus”, “dermatophyte”, “parasite”, “infestation”, “immunosuppression” and “immuno- deficiency”. Articles published in English, German and French were included. The search run included Jan 1982 until Dec 2020 (Fig. 1).

No ethical commission approval was required as no direct patient data were involved. The patient’s authorization was obtained for the publication of clinical pictures.

3. RESULTS

A total of 90 articles were retrieved describing skin infections with a VC-PEH presentation. In many cases, the VC-PEH pattern was considered an atypical manifestation of the cutaneous infection. Among these were disclosed 5 parasitic skin diseases (Scabies, Leischmaniasis, Amebiasis, Tungiasis, and pinworm), 6 viral agents (Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Pox and parapoxviridae, Polyomaviridae and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), 10 bacterial agents and diseases (Actinomyces, Mycobacteria (Marinum, Ulcerans, Malmoense, Leprae, Tuberculosis), Treponema, Bartonella, Donovanosis and Serratia marcescens) and 12 fungal agents (Paracocci- dioidomycosis, Blastomycosis, Malassezia, Candidiasis, Chromoblastomycosis, Sporotrichosis, Scedosporium, Trichophyton rubrum, Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillosis, Lacazia and Alternariosis).

Another typical feature was that all VC-PEH lesions were longstanding and that the diagnostic delay was important.

Table 1 summarizes the name of the disease (when available), the infectious agent, the sampling method used for diagnosis, the main identification techniques, comorbidities, and the treatment prescribed for the VC-PEH lesions, according to the ad hoc articles.

|

Disease Infectious Agent |

Sampling Method |

Immuno suppression |

Diagnostic Method | Treatment | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial agents | |||||

| Fish tank granuloma Mycobacterium Marinum |

Skin biopsy Swab |

ND | Ziehl, PCR Culture |

Minocyclin 100mg/d 2-3 months | [54] |

| Tuberculosis Mycobacterium Tuberculosis | Skin biopsy | - | Tuberculoid granulomas PCR | Isoniazid 75 mg, Pyrazinamide 400 mg Rifampicin 150 mg Ethambutol HCL 275 mg/d. 5 months | [55-60] |

| Tuberculoid lepra Mycobacterium Leprae (Hansen bacilla) | Skin biopsy Smear of dermal exsudate |

- | H/E, PCR with MntH-specific primers for M. leprae, Bacilloscopy with Ziehl-Neelsen, Fite-Faraco stains, IHC with antibodies against bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and phenolic glycolipid antigen-1 (PGL-1) |

Rifampicin 600mg monthly, Dapsone 100mg/d 6 months |

[52, 53] |

| Buruli ulcer Mycobacterium ulcerans |

Skin biopsy | - | Ziehl-Neelsen | Rifampycine 600mg/d Clarithromycine |

[61, 62] |

| Mycobacterium malmoense | Skin biopsy | - | Ziehl-Neelsen: Necrotizing granulomas, with giant cells DNA testing: Genotype Common Mycobacteria (GenoType CM) and GenoType Additional Species |

Rifampicin, Ethambutol, Isoniazid and Pyrazinamide | [63] |

| Actinomyces | Skin biopsy | Yes | Gram stain, filaments of actinomyces Culture |

IV Penicillin G 6 weeks followed by oral Penicillin V for 12 months | [43, 44] |

| Syphilis Treponema pallidum |

Skin biopsy Swab Serology |

ND | PCR PCR VDRL, TPHA, FTA, (PCR) |

IM Penicillin G | [45-49] |

|

Bartonella henselae Bartonella quintana Bacillary angiomatosis |

Skin biopsy | - | Warthin-Starry and Giemsa staining revealing clumps of coccobacilli. | Doxycycline 200 mg 12 weeks, Macrolide with addition of rifampicin or gentamycin |

[64, 65] |

| Serratia marcescens | Skin biopsy Swab |

- | Giemsa Culture |

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 960 mg every 12h, 20 days | [66] |

|

Klebsiella granulomatis Donovanosis Granuloma inguinale |

Swab Skin biopsy |

- | Intracellular and extracellular Donovan bodies Giemsa stain, culture, PCR | Azithromycin 2x500 mg/week, 3 weeks. Doxycycline 200 mg/d, 21 days. | [67] |

| Fungal agents | |||||

| Chromoblastomycosis Fonsecaea pedrosoi and compacta, Cladosporium carrionii, Phialophora verrucose, Rhinocladiella aquaspersa, Exophilia spinifera, Exopilia pisciphila |

Smear Scraping Skin biopsy |

- | Sclerotic, fumagoid cells Culture Fumagoid cells, PCR |

Itraconazole | [78-84] |

| Blastomycosis Blastomyces dermatitidis |

Skin biopsy | - | Periodic acid-Schiff, Grocott’s methenamine silver large spherical double contoured 8-15 µm multinucleated yeast. Budding forms have a characteristic broad base. | Itraconazole Voriconazole Posaconazole Fluconazole |

[3] |

| Sporothrix schenckii | Smear Skin biopsy |

- | Levuriform elements (cigar bodies), asteroid bodies Culture Sabouraud PAS, Gomori-Grocott, IF |

Itraconazole 100-400mg/d | [85, 86] |

| Candida Albicans | Smear Skin biopsy |

Yes | Culture | Itraconazole Fluconazole |

[3, 72-77] |

| Scedosporium | Skin biopsy | - | - | Oral voriconazole 200 mg, 2x/d 12 weeks | [87] |

| Trichophyton rubrum | Skin scraping Skin biopsy |

Yes | Culture, direct examination KOH30%, PAS, myceliums H/E, PAS |

Terbinafine Itraconazole |

[71] |

| Malassezia | Skin scraping Scotch test Skin biopsy |

- | Yeasts grouped in clusters and short thick-walled filaments | Itraconazole | [49] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Oral biopsy | Yes | - | Itraconazole 100-400mg/d | [69, 70] |

| Aspergillosis | Skin biopsy | Yes | Septate hyphae with dichotomous branching | Voriconazole | [90] |

| Alternaria | Skin biopsy | Yes | Fungal structures with a typical round-to-oval, thick refractile wall | Itraconazole 100-400mg/d | [91] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Skin biopsy | Yes | - | - | [89] |

| Lacazia loboi | Skin biopsy | ND | Spherical, double-walled structures, appearing isolated or grouped in chains. Grocott staining | Surgical excision + oral itraconazole 200 mg/d | [92] |

| Parasitic agents | |||||

| Leishmaniasis | Skin biopsy Skin scraping |

Immunosuppresion? | Leishman bodies in macrophages, Giemsa Amastigotes, May-Grüwald-Giemsa |

No established guidelines. Pentavalent antimonials: first line treatment | [9-11] |

| Crusted scabies Scabies |

Skin biopsy, Skin scraping |

Yes | Mites, ova, or faecal pellets, H/E | Permethrine cream Ivermectin PO |

[6-8] |

| Amebiasis Entameoba histolytica |

Skin biopsy | ND | Antigen detection, PCR | Metronidazole PO or IV at 250–750mg every 8–12 hours | [12, 13] |

| Tungiasis Tunga penetrans |

Skin biopsy | ND | Presence of tunga | As early as possible extraction of the flea | [14] |

| Pinworm Enterobious vermicularis |

Skin biopsy | ND | Presence of pinworms | Mebendazole Pyrantel embonate Pyrvinium embonate | [15] |

| Viral agents | |||||

| Chronic HSV infection HSV-1, HSV-2 |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E, IHC (IE proteins), PCR | TK-dependent antivirals, ACV, VCV, FCV Foscarnet Cidofuvir Imiquimod Thalidomide |

[16-23] |

| Chronic VZV infection VZV |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E, IHC (IE63), PCR | TK-dependent antivirals, ACV, VCV, FCV Foscarnet Cidofuvir Imiquimod Thalidomide |

[16, 21, 24] |

| Trichodysplasia spinulosa TS-Polyomavirus |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E, PCR (T-antigen DNA) | Valganciclovir cidofovir Reduction of immunosuppression |

[40-42] |

| Milker’s nodule, Orf Poxvirus, Parapoxvirus |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E, IF, PCR |

Imiquimod Extraction |

[8, 36-39] |

| Viral warts HPV |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E IHC (Common Papillomavirus Antigen) ISH (HPV subtyping) PCR (HPV subtyping) |

Destructive therapies Imiquimod Topical keratolytics |

[5, 31-35] |

| Oral hairy leukoplakia EBV |

Skin biopsy | Yes | H/E ISH (EBV (EBER) DNA Probe/Fluorescein), IHC (EBV-EBER nuclear stain indicating active EBV infection, EBV-LMP staining indicating latent infection PCR (automated Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) PCR assays) |

Topical keratolytics Topical retinoids CO2 laser |

[25-30] |

3.1. Parasitic Causes

3.1.1. Crusted Scabies

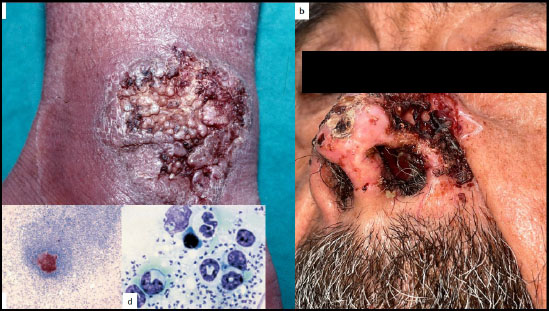

Profuse PEH with fissuring and bleeding may be observed in patients with crusted scabies (CS), a rare but severe and chronic form of scabies [6], (Fig. 2a-c). The parasitic load of the epidermis is extremely high, reaching thousands of parasites. Debilitation or the inability to scratch and mechanically remove infected scabs may furthermore increase the proliferation of the parasites. Nearly all published cases of CS were linked to a certain degree of immunodeficiency, or observed in debilitated, neurologically, or mentally ill patients [7]. Patients with CS present a deficient Th2 immune response. They also present an absence of B lymphocytes or specific antibodies but demonstrate a high number of T lymphocytes with a high CD8+/CD4+ratio, presuming a primordial role of cytotoxic CD8+T-cells. In contrast, classic scabies skin lesions present CD4+T-cell counts four times higher than that for CD8+T-cells. The precise role of cytotoxic T cells in CS is not yet clear. They might play a role in the proliferation of keratinocytes [6]. Furthermore, there is an inadequate local immune response with local hypersecretion of IL17, which is responsible for an increased epidermal renewal with hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, as observed in psoriasis [8]. The PEH pattern in CS could also represent a reactive pattern to scratching or seen as an epidermal defense mechanism against the high charge of parasites in the epidermis (Fig. 2c).

a: Crusted scabies of the dorsal aspect of the hand, b: of the face and neck, c: histology evidencing the PEH pattern (blue arrows) and the sarcopte (yellow arrows).

a): Leischmaniosis in PEH form of the dorsal aspect of the wrist, b): of the nose, c): granulomatous reaction against Leischman bodies, d): amastigote bodies in dermal macrophages.

3.1.2. Leishmaniasis

The VC-PEH pattern during cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) seems to be not exceptional as up to 45% of the cases present with a chronic PEH squamous hyperplasia and verrucous reaction (Fig. 3a, b). It is probably a response to chronic epithelial irritation. The ever-increasing use of immunosuppressive agents led to an important geographical expansion of CL in the last 20 years. In particular, the TNF antagonists increase the risk of opportunistic infections, such as leishmaniasis, due to their inhibitory action on granulomatous reactions. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) should be excluded [9, 10]. Another publication confirmed the high incidence of VC-PEH in CL. In a multiregional study including 396 CL patients, 71.8% of the patients showed extensive disease with 15.7% more than 12 months duration. Histology revealed a granulomatous inflammation pattern in 55.5% of the cases, interface changes (72.7%), spongiosis (75.3%), as well as a marked PEH (63.9%) [9, 11]. Histology of verrucous CL lesions reveals PEH with sometimes central ulceration, the presence of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes, as well as the presence of amastigotes in dermal macrophages (Fig. 3c, d).

3.1.3. Amebiasis

Amebiasis is a parasitic infection by Entamoeba histolytica of the gastrointestinal tract with, exceptionally, a possible extension to the skin where verrucous plaques may be observed. Histologically, the verrucous lesions reveal an irregular, more or less severe PEH [12]. They are typically poor in the number of trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica [13].

3.1.4. Tungiasis

Tungiasis is caused by the penetration of the female sand flea Tunga penetrans into the epidermis and subsequent hypertrophy of the parasite. In most cases, lesions are confined to the feet. Histology may show a PEH aspect of the epidermis [14].

3.1.5. Pinworm

Enterobious vermicularis is a form of pinworm infestation that has been reported to present with a VC-PEH pattern on the vulva [15].

3.2. Viral Causes

3.2.1. HSV and VZV

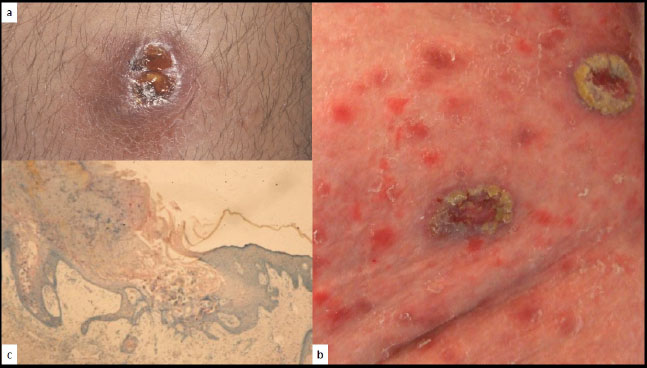

Mucocutaneous wart-like with or without central ulceration can be encountered during chronic herpes simplex virus (CHSV) (Fig. 4a, b) and chronic varicella zoster virus (CVZV) infections [16-19], (Fig. 5a, b).

They are nearly always associated with HIV infection but sometimes with other types of immunosuppression, like organ transplant recipients (OTR) or exceptionally in immunocompetent individuals. Their clinical expression is highly polymorphous and makes diagnosis difficult. CHSV are usually observed in the anogenital area [19]. Histology reveals various degrees of EH and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, usually without the presence of cytopathic effects, rendering the histological diagnosis even more complicated (Fig. 5c). Immunohistology with specific anti-HSV and anti-VZV antibodies (preferentially anti-IE protein antibodies), in situ hybridization (ISH), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and additionally viral culture are required to establish the diagnosis [16]. Resistance to thymidine kinase (TK)-dependent antivirals is usual [16]. Other atypical histological patterns during CHSV infection have been reported in the form of a slightly acanthotic epidermis with focal ulceration, dense dermal sclerosis, scattered plasma cells and a brisk lympho-eosinophilic infiltrate with dissection between dense collagen bundles [20]. Another publication described 9 HIV patients with CHSV presenting as tumor-like nodules or condylomatous or hypertrophic lesions with scrotal or vulvar masses or perianal nodules. Histopathology evidenced a dense dermal plasmocytic infiltrate with overlying PEH, superficial ulcers and classic herpetic inclusions [21, 22]. Neoplasia (cSCC) should always be excluded in the event of CHSV [23].

In sum, CHSV should be excluded in the case of any VC-PEH pattern, particularly when the lesion affects the anogenital area of an immunocompromised individual.

a: Isolated hyperkeratotic chronic genital herpes lesion, b: profuse verrucous chronic genital herpes lesions.

a: Isolated chronic verrucous VZV lesion, b: multiple verrucous VZV lesions, c: verrucous pattern (H/E x 10).

CVZV infection may be observed on the entire tegument with the same clinical heterogenicity as CHSV [16, 24]. Diagnostic methods are identical to those used for CHSV. TK-related antiviral resistance is also common [16].

It is still not determined whether the CHSV and CVZV-related VC-PEH patterns are due to an atypical viral relationship with the host cell, like a low-permissive infection without apoptosis of the host cell, or merely represent a reactive pattern of the epidermis to the chronic infection [21].

EBV-related oral hairy leukoplakia in a HIV patient (blue arrows).

3.2.2. EBV

Among the mucocutaneous infections caused by EBV, oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) may present a linear VC-PEH pattern (Fig. 6), typically occurring on the lateral aspect(s) of the tongue, particularly in HIV patients [25-28]. Histologically, OHL is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, with a lack of inflammatory cells [29]. There are areas of ballooning cells and a few pyknotic nuclei with inclusions [30]. The VC-PEH pattern is not pathognomonic for OHL. The diagnosis is best performed using specific EBV nuclear probes for ISH, PCR, or IHC on tissue samples.

3.2.3. HPV

According to the HPV type, the clinical and histological aspects differ, although the underlying pathomechanisms are similar [31]. Common warts (HPV 1,2,4), butcher’s warts (HPV 2,7), condylomata acuminata (HPV 6,8,11), the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor (HPV 6,11) [32], (Fig. 7a), focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck’s disease) (HPV 13,32) [33, 34], Bowenoïd papulosis (HPV 16,18) are all different clinical manifestations of various alpha-HPV mucocu- taneous infections. Epidermodysplasia verruci- formis (EV) is the most common form of cutaneous verrucosis and is typically associated with alpha-HPV 5 and 8 infection [35].

The HPV productive infection and induction of hyperproliferation are initiated when the virus enters the basal cell layer. The HPV E5, E6, and E7 proteins induce the epidermal cell cycle to continue. In combination with other proteins, the E6 protein causes the degradation of the cellular p53 protein, hence removing the brake on supra-basal cell cycling, leading to hyperproliferation [35].

The combination of the clinical aspect, the localization and the histological pattern, in particular the presence of koilocytes, orient the pathologist towards HPV infection, but the final diagnosis relies on the ISH or PCR identification of the responsible HPV subtype.

Again, when a VC-PEH pattern is disclosed in association with an HPV infection, for example, the Buschke-Löwenstein tumor (Fig. 7a, b) or epidermodyplasia verruciformis associated lesions, there is nearly always an underlying immunosuppressive condition.

a: Buschke-Löwenstein tumor of the vulva, b and c: histology revealing the PEH pattern (H/E, x 10, x 40)(Courtesy to Dr Dr. Neagu Iuliana Mihaela and Prof. Dr. Rotaru Maria).

a: Milker’s nodule, b: Orf.

3.2.4. Poxvirus

Milker's nodule virus, also termed paravaccinia virus, is a DNA virus of the parapoxvirus genus that is transmitted from infected cows to humans. An erythematous nodule with a depressed center develops 5 to 15 days after inoculation. Milker's nodules are usually self-healing in immunocompetent individuals and heal without scarring within 2 months (Fig. 8a). However, in some instances, Poxviridae may present with a VC-PEH pattern, especially in immunocompromised patients, such as giant molluscum contagiosum [36].

The Orf virus is also transmitted from animals to humans by direct contact [37]. These parapox viruses may present complicated and atypical clinical presentations, especially in immunocompromised patients [38]. The Orf virus may also present with a VC-PEH pattern (Fig. 8b). Diagnosis is usually made on a clinical basis [39].

Both Milker’s nodule and Orf are easily diagnosed on a histological sample by the presence of typical eosinophilic inclusions [37].

More recently, cases of monkeypox infection in immunocompromised patients have been reported with a VC-PEH pattern (Fig. 9).

Monkeypox infection with a PEH appearance in an HIV-infected individual: a: of the nose, b: on the thorax.

3.2.5. Polyomavirus

Certain members of the polyomavirus (PyV) family may also be responsible for VC-PEH patterns [40], such as the Trichodysplasia Spinulosa polyomavirus (TS-PyV). TS is rare and is nearly exclusively encountered in patients with longstanding immunosuppression, specifically in OTRs. TS is characterized by increased proliferation of inner root sheath keratinocytes and keratin spine formation, leading to a folliculo-centric papular eruption of the face that may evolve into leonine facies. TS presents with distinct histological features, including the presence of large eosinophilic, trichohyaline granules within the hyperproliferating inner root sheath cells of the hair bulb [41, 42].

3.3. Bacterial Causes

3.3.1. Actinomycosis

Primary cutaneous actinomycosis is a chronic bacterial infection, usually caused by Actinomyces israelii. The infection typically affects the cervico-facial region. Histologically, the wart-like lesions show a pseudo- epitheliomatous hyperplasia or acanthosis [43]. The characteristic Actinomyces granules can be found using Gram’s histochemical stain. In patients with HIV infection, actinomyces may present as an atypical, longstanding wart-like lesion [44].

3.3.2. Treponema Pallidum

Yaws present clinically as a wart-like growth and is caused by the primary stage of the non-venereal Treponema pallidum pertenue skin infection [45]. The early lesions may exhibit significant papillomatosis. Silver histochemical stains readily identify the treponemes. In the second stage of endemic syphilis, Treponema pallidum endemicum may present as verruciform flat condylomata.

Even some cases of syphilitic chance or late secondary syphilis may resemble verrucous lesions called condyloma lata [46-49].

3.3.3. Mycobacterium Family

Cutaneous mycobacterial infections present with widely different clinical presentations, including cellulitis, non-healing ulcers, subacute or chronic nodular lesions, abscesses, superficial lymphadenitis and verruciform lesions [50, 51]. Skin biopsies of cutaneous lesions to identify acid-fast staining bacilli and cultures represent the cornerstone of diagnosis. Molecular assays are useful in some cases.

3.3.4. Mycobacterium Leprae

In some instances, tuberculoid leprosy may present as wart-like lesions [52] with an VC-EH pattern (Fig. 10). A patient is described who presented an anesthetic well-demarcated, erythematous and mildly scaly plaque on his right forearm. The histological aspect revealed a compact tuberculoid granuloma with a hyperkeratotic epidermis, regular acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and cells with abundant basophilic cytoplasm. A Ziehl-Neelsen staining demonstrated the presence of rare acid-fast bacilli and confirmed the tuberculoid leprosy diagnosis [53].

Verrucous lesions of lepra of the legs (blue arrows).

3.3.5. Mycobacterium Marinum

In a case series of 15 cases with M. marinum related fish tank cutaneous infection of the upper limbs, one-fifth of the patients presented with a single papulo-verrucous lesion. The diagnosis was achieved by history, clinical examination, histology, culture, acid-fast bacilli identi- fication from the histologic specimen, and by PCR [54].

Verrucous tuberculosis of the hand.

3.3.6. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Cutaneous lesions of tuberculosis infection may present in a verrucous form called tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (Fig. 11), [55-59]. As always in longstanding inflammatory lesions, cSCC should be excluded. A 72-year-old man presented with a chronic scaly verrucous plaque over his right knee for nine months that turned out to be a cSCC arising from tuberculosis verrucosa cutis within a significantly shorter time interval than usual [60].

3.3.7. Mycobacterium Ulcerans

Buruli ulcer is an indolent skin infection caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans [61]. In some instances, they may present with VC-EH patterns [61, 62], (Fig. 12a-c). PEH of the epidermis occurring with Mycobacterium ulcerans skin infection may result in localization of the infected area with a discharge of necrotic material, followed by healing, leaving a depressed scar. The process represents more than a simple re-epithelization of an ulcerated skin surface; there is an active extrusion of necrotic material containing viable mycobacteria and should be seen as part of a protective physiological skin response to the infection [62].

3.3.8. Mycobacterium Malmoense

Cutaneous infections by Mycobacterium malmoense are rare and the usual clinical presentation is nodular skin lesion, but cases presenting with a VC-PEH pattern have been reported [63].

3.3.9. Bartonella

Bacillary angiomatosis is a rare hyperproliferation of endothelial cells caused by Bartonella henselae. In some instances, bacillary angiomatosis may be associated with PEH [64]. Bartonella quintana has been reported in a case of vulvar VC-PEH [65].

3.3.10. Serratia Marcescens

An elderly woman's VC-PEH pattern was observed on the dorsal aspect of her left hand. Histology revealed PEH and a dense dermal infiltrate largely composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes. Abscess formation and fibroblastic proliferation were also present. Fite, Giemsa, and periodic acid-Schiff histochemical stains did not reveal specific organisms. The gram-negative bacillus Serratia marcescens was the only microorganism isolated from all cultures [66].

3.3.11. Donovanosis

The VC-PEH pattern is observed in some cases of granuloma inguinale or donovanosis infection by Klebsiella granulomatis [67]. Giemsa histochemical stain readily identifies intracellular and extracellular Donovan bodies.

3.4. Fungal Causes

Hyperkeratosis of the feet is common, and it often coincides with fungal infections and is difficult to treat and relapse rates are high [68]. Wart-like appearances due to fungal agents are described hereunder.

3.4.1. Paracoccidioidomycosis

Oral and skin lesions containing paracocci- dioidomycosis may present with a VC-PEH pattern in immunocompromised patients, especially AIDS patients [69, 70], (Fig. 12).

3.4.2. Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis, due to Blastomyces dermatitidis, can lead to VC-PEH lesions in the oral cavity [3].

3.4.3. Malassezia

Malassezia skin infections are usually present as seborrheic dermatitis or pityriasis versicolor. One publication mentioned 3 young women who presented wartlike lesions of the nipples that were associated with Malassezia yeasts [71].

3.4.4. Candidiasis

In some instances, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis [72-74] may present with hyperplastic verrucous lesions (Fig. 13), [3, 75-77], typically occurring in the immunodeficient patient. Itraconazole oral therapy seems to be the first-line therapeutic choice [74].

Buruli’s ulcerated PEH lesions of the a: leg, b: dorsal aspect of the hand and, c: knee.

Paracoccidiomycosis-related PEH ulcerated lesion of the chin.

3.4.5. Chromoblastomycosis

Chromoblastomycosis is a rare chronic fungal infection affecting the skin and subcutaneous tissues. It primarily occurs in tropical and subtropical regions. Chromo- blastomycosis is typically observed among agricultural workers following trauma to vegetables. On occasion, cutaneous chromoblastomycosis may clinically present as hyperpigmented verrucous lesions (Fig. 14). They are typically chronic and may present histologically as a pseudoepitheliomatous growth [78-82]. Histopathology reveals the presence of a high number of classical copper penny bodies or muriform bodies and a predominantly neutrophilic dermal infiltrate [83].

Chronic verrucous candidiasis in an immuno- compromised patient.

Rhinocladiella aquaspersa was identified in a patient with verrucous plaques, Itraconazole and posaconazole displaying the highest in vitro activity [84].

3.4.6. Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is a cutaneous mycosis caused by a dimorphic fungus, Sporothrix schenckii species, typically presenting as an erythematous papule, the nodulo-ulcerative lesion usually occurring at the site of penetrating trauma, mostly on the extremities. A verrucous aspect (Fig. 15) is a rather rare presentation of sporotrichosis potentially mimicking wart-like lesions as observed in chromoblastomycosis, tuberculosis verruca cutis, CL and blastomycosis. One case of a young child from the sub-Himalayan region with facial verrucous sporotrichosis has been documented [85, 86].

Verrucous chromoblastomycosis on the arm.

3.4.7. Scedosporium

A longstanding verrucous plaque on the wrist of a 13‐year‐old Hispanic boy without any significant medical history and previously unsuccessfully treated with oral itraconazole and terbinafine was demonstrated to be linked to cutaneous scedosporium infection [87].

3.4.8. Trichophyton Rubrum

Trichophyton rubrum is one of the most common fungal infections in humans and usually presented as an athlete's foot with fissuring in the fourth interdigital space or as an intertriginous erythemato-squamous lesion. Even in immunocompromised individuals, the clinical presen- tation is usually like that observed in immunocompetent subjects. A verrucous lesion due to T. Rubrum has been described in an AIDS patient [88].

3.4.9. Fusarium Oxysporum

Fusarium species infections in humans are usually favored by immunodeficiency and may present as mycetomas. One case presenting with a hyperkeratotic verrucous wart-like skin lesion on the foot has been reported in a 50-year-old immunocompetent farmer [89].

3.4.10. Aspergillosis

A burn patient was described with VC-EH linked to cutaneous aspergillosis of the axilla. Histology revealed an irregular proliferation of the epidermis, invaginating deeply into the dermis with an intense inflammatory reaction within the superficial and deep dermis. Numerous fungal forms were identified within the dermis. Special staining demonstrate septate hyphae with dichotomous branching, morphologically indicative of Aspergillus infection [90].

3.4.11. Alternariosis

In OTR patients, the opportunistic fungus Alternaria presents with a VC-EH pattern in up to 50% of the cases [91].

3.4.12. Lacaziosis

Lacaziosis, also termed Jorge Lobo’s disease, is a fungal disease caused by Lacazia loboi, which usually affects the skin and subcutaneous tissues [92]. It slowly progresses after inoculation and can present with a VC-EH form (Fig. 16, 17). Histopathology with Grocott’s staining confirms the diagnosis of lacaziosis by identifying spherical, double-walled structures, that appear isolated or grouped in chains.

Verrucous sporotrichosis.

Verrucous lacaziosis.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Sampling Methods and Diagnostic Techniques

Due to the hyperkeratotic character of these VC-EH lesions, the most frequently used sampling method reported in the literature is a skin biopsy of the epithelial border. Excision of the entire lesion, if surgically reasonable, remains a golden standard, providing the optimal chance to recover the causal agent. Identification is then performed using various histochemical stains, IHC, ISH, and/or PCR (Table 1). When lesions become necrotic or present central ulceration, a swab may be performed to identify the causal infectious agent, although the sensitivity of swabbing is often lower than a skin biopsy. Superficial swabbing could also identify opportunistic but not causal microbial agents and hence lead to erroneous therapy. As some of these infections have a very poor load of microorganisms, it is recommended to provide the laboratory with fresh and large (excisional) biopsy specimens. cSCC should always be ruled out [93].

4.1.1. Pathomechanisms

The VC-PEH pattern seems to be highly heterogenous, both clinically and histologically. The pattern is not specific to a particular infectious agent. Except for the HPV, Polyomavirus, EBV, Poxvirus, and parapoxvirus-induced forms of VC-PEH, the other viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic infectious VC-PEH patterns seem to be reactive processes, related in general to a chronic, longstanding infection.

Another emerging theory is that chronic skin/ epidermal infections cause a modification in the cutaneous microbiome, especially concerning a reactivation of the beta-papillomaviridae. In fact, the latter may cause the proliferation of keratinocytes in immunocompromised cutaneous districts.

Some authors put forward the hypothesis that the VC-PEH pattern is a defense mechanism involving trans-epidermal elimination of microorganisms affecting the skin and should be considered as part of a protective physiological response to the infection.

4.1.2. Treatments

In the event of the presentation of infectious diseases with a VC-PEH pattern, no established guidelines for the above-mentioned infectious agents, except for chronic HSV and chronic VZV skin lesions [16] are established. Table 1 resumes the treatment option(s) that were used in the cited articles. Usually, the treatments recommended were like those used for the classic presentations of different infectious agents. No reliable data were found on particular dosing regimens and treatment duration.

CONCLUSION

This review suggests that infectious agents should be searched for in a patient with longstanding verrucous lesions, with or without central ulceration, demonstrating a histological pattern of EH, in particular in the event of immunosuppression. Skin biopsies of the epithelial border or, preferentially, an excisional biopsy seem to be the most frequently recommended sampling method for the diagnosis of VC-PEH. There is a difference in therapeutic attitude between viral VC-PEH and other organisms originated VC-PEH, as the diagnosis of viral VC-PEH is more straightforward and hence the treatment is clearcut whereas other organisms related VC-PEH is much less easy to diagnose and hence treatment will often be delayed. Treatment of VC-PEH cases relies on the standard of care according to the underlying microorganism.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

D.T. and N.A.F.: Study conception and design and manuscript draft were contributed; O.-R.M., B.M., R.M.A., S.B.O., M.M. and T.N.: Data were collected; L.F., L.E., D.G. and C.P.: Analysis and interpretation of results were provided.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PEH | = Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia |

| HPV | = Human papillomavirus |

| VC | = Verruciform/crateriform aspect |

| EBV | = Epstein-Barr Virus |